Note: This article discusses the former morphological classification system of bacteriophages. This system is no longer used and has been replaced by a more standardised taxonomy. You can read our updated article here, where we also feature an interview with the Vice President of the ICTV, Dr. Evelien Adriaenssens.

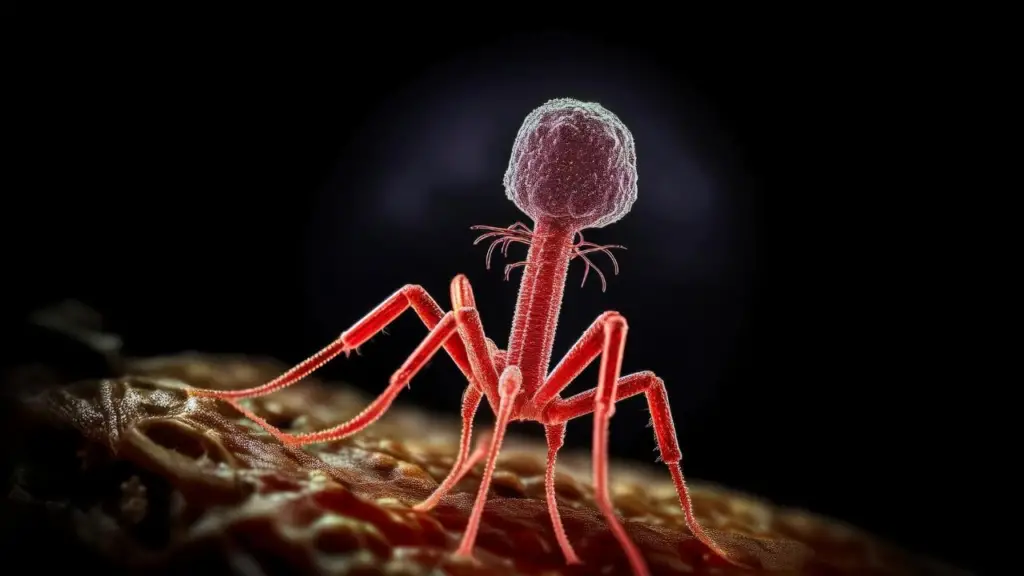

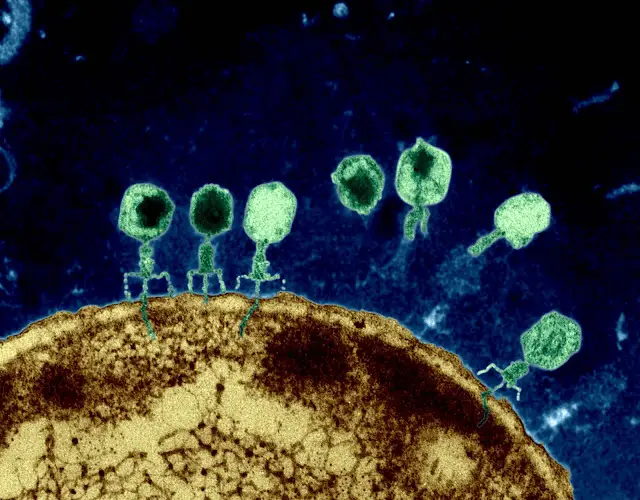

In both academic and non-academic settings, bacteriophages are often represented using the familiar “classic” shape—a particle with a distinct head, a contractile tail composed of the neck, sheath, baseplate, and pins, and long tail fibres. This iconic image, inspired largely by the T4 bacteriophage, has become the default mental picture when most people think of phages.

However, this morphology represents only one branch of phage diversity. While some bacteriophages share similar overall structures—with variations in proportions or the presence or absence of certain tail structures—many others look entirely different. Some phages are long, filamentous “thread-like” particles (e.g., Inoviridae), others are spherical or pleomorphic (e.g., Cystoviridae), and some are simple icosahedral capsids without tails (e.g., Leviviridae).

Phage morphology can still provide useful descriptive information, especially when genomic or protein-level data are not available. However, modern taxonomy no longer relies on morphology alone, as many unrelated viruses can share similar shapes.

There are several ideas about why the T-phage morphology has become the most widely used graphical representation of bacteriophages. While T-even phages were not the first to be discovered, they were among the earliest to be visualised in great detail using electron microscopy, which made them iconic in early virology textbooks. Their clearly defined structural components, head, tail, baseplate, and fibres, also made them ideal models for studying phage assembly and infection mechanisms.

In addition, tailed phages (Caudoviricetes) represent a large proportion of known bacterial viruses, which may have reinforced the use of the T-phage silhouette as the “default” phage illustration. Some have also argued that its striking, machine-like appearance intuitively conveys the idea of a virus hunting and infecting bacteria.

Although this morphology is visually memorable and historically influential, it represents only one group within a much broader and more diverse phage world.

Scientists are revealing a lot of important information that we would have missed in previous decades as sophisticated improvements in science and technology positively impact research. Although the age of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) has reignited interest in bacteriophage research, many scientists around the world are working together to find antibiotic alternatives. Much information has been released/revealed during this time, and humanity is now becoming more acquainted with their close “ally” in the microscopic universe (bacteriophages). The less prioritized phage morphologies are now in the spotlight as well.

Bacteriophage classification by morphology (shapes)

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses is in charge of virus (including phage) classification (ICTV). This body has proposed a morphology-based classification system. This version of classification is simpler than Bradley’s (which will be discussed later) and contains only four groups: polyhedral or cubic, filamentous or pleomorphic phages.

Classification of bacteriophages based on morphologies as per the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV)

Tailed phages (equivalents to 96% of the phages discovered)

Classified as order Caudovirales, divided into three families: Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, and Podoviridae.

| Bacteriophage family | Example |

|---|---|

| Myoviridae phages- with icosahedral heads, contractile tails, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) | Phage T4 Phage P1 |

| Siphoviridae phages -with icosahedral heads, long and non-contractile tails, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) | Phage λ Lactococcus phage C2 |

| Podoviridae phages- have an icosahedral head, short tails, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) | Phage T7 Phage P22 |

Polyhedral or cubic phages

-classified into Microviridae, Corticoviridae, Tectiviridae, Leviviridae, and Cystoviridae.

| Bacteriophages family | Example |

|---|---|

| Microviridae phages- icosahedral head, virion size 27 nm, with 12 capsomers, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) | Phage φX174 |

| Corticoviridae phages- no envelope, 63 nm in size, complex capsid, lipids, dsDNA | Phage PM2 |

| Tectiviridae phages- no envelope, 60 nm, flexible lipid vesicle, pseudo-tail, dsDNA | Phage PRD1 |

| Leviviridae phages- no envelope, 23 nm, poliovirus-like, ssRNA | Phage MS2 |

| Cystoviridae phages-with enveloped, icosahedral head, 70-80 nm, lipids, dsRNA | Pseudomonas ɸ6 |

Filamentous phages

It-Made up of three families known as Inoviridae, Lipothrixviridae, and Rudiviridae.

| Bacteriophage family | Example |

|---|---|

| Inoviridae phages- no envelope, long flexible filament or short straight rods, ssDNA | Phage M13 |

| Lipothrixviridae phages- enveloped, rod-shaped capsid, lipids, dsDNA | Phage TTV1 |

| Rudiviridae phages- Straight uncoated rods, TMV-like, dsDNA | Phage SIRV-1 |

Pleomorphic phages

Phages containing dsDNA are classified into several families: Plasmaviridae, Fuselloviridae, Guttaviridae, Bicaudaviridae, Ampullaviridae, and Globuloviridae.

| Bacteriophages family | Example |

|---|---|

| Plasmaviridae phages- enveloped, 80nm, with no capsid, lipids | Phage MVL2 |

| Fuselloviridae phages- enveloped, tapered capsid with short spikes end, lipids. | Phage SSV1 |

| Ampullaviridae phages- enveloped, bottle-shaped virion, 230 nm in length | Phage ABV |

| Guttaviridae phages- droplet-shaped | Phage SNDV |

| Bicaudaviridae phages- Lemon-shaped virions, 120X 80 nm, long tails | Phage ATV |

Many scientists came up with different ways of classifying phages. However, the most popular style was the one published by Bradley in 1967which resulted in six bacteriophage-based on six morphological groups, with the seventh group added later by other scientists.

Classification of bacteriophages based on morphologies as described by Bradley (1967)

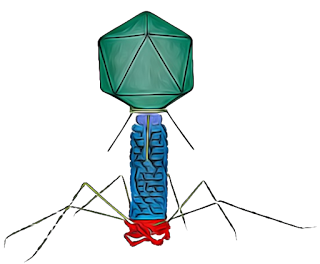

Type A: Bacteriophage with hexagonal head and tail with contractile sheath

These viruses have a “tadpole shape,” meaning they have a hexagonal head, a rigid tail with contractile sheath and tail fibers dsRNA, and T-even (T2, T4, T6) phages. Most of the phages are T-shaped.

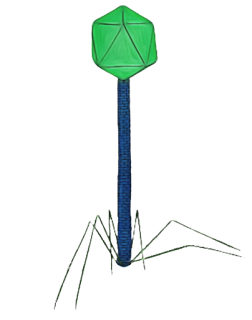

Type B: Bacteriophage with a hexagonal head and long, flexible tail

Unlike Type-A, these phages contain a hexagonal head, but they lack a contractile sheath. Its tail is flexible and may or may not have tail fiber, such as dsDNA phages, e.g., T1 and T5 phages.

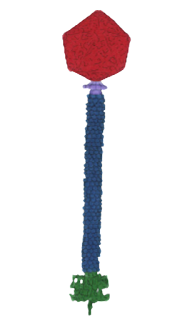

Type C: Bacteriophage with a hexagonal head and short, non-contractile tail

Type C is characterized by a hexagonal head and a tail shorter than the head. The tail lacks contractile sheath and may or may not have tail fiber, such as dsDNA phages, e.g., T3 and T7.

Type D: Bacteriophage with only hexagonal head in symmetry with large capsomere on it

Type D contains a head made up of capsomers but lacks a tail, for example, ssDNA phages (e.g., φX174). The capsomeres are subunits of the capsid, an outer covering of protein that protects the genetic material.

Type E: Bacteriophage with a simple regular hexagonal head

This type consists of a head made up of small capsomers but contains no tail, for example, ssRNA phages (e.g., F2, MS2).

Type F: Bacteriophage with no head but with long flexible filament virion

These phages are named for their filamentous shape, a worm-like chain, about 6 nm in diameter and about 1000-2000 nm long.

Type G: No detectable capsid (This group was added later after Bradley’s original study publication)

This group has a lipid-containing envelope and has no detectable capsid, for example, a dsRNA phage, MV-L2.

Credit: Drawn by Omar Cots Fernandez for The Phage

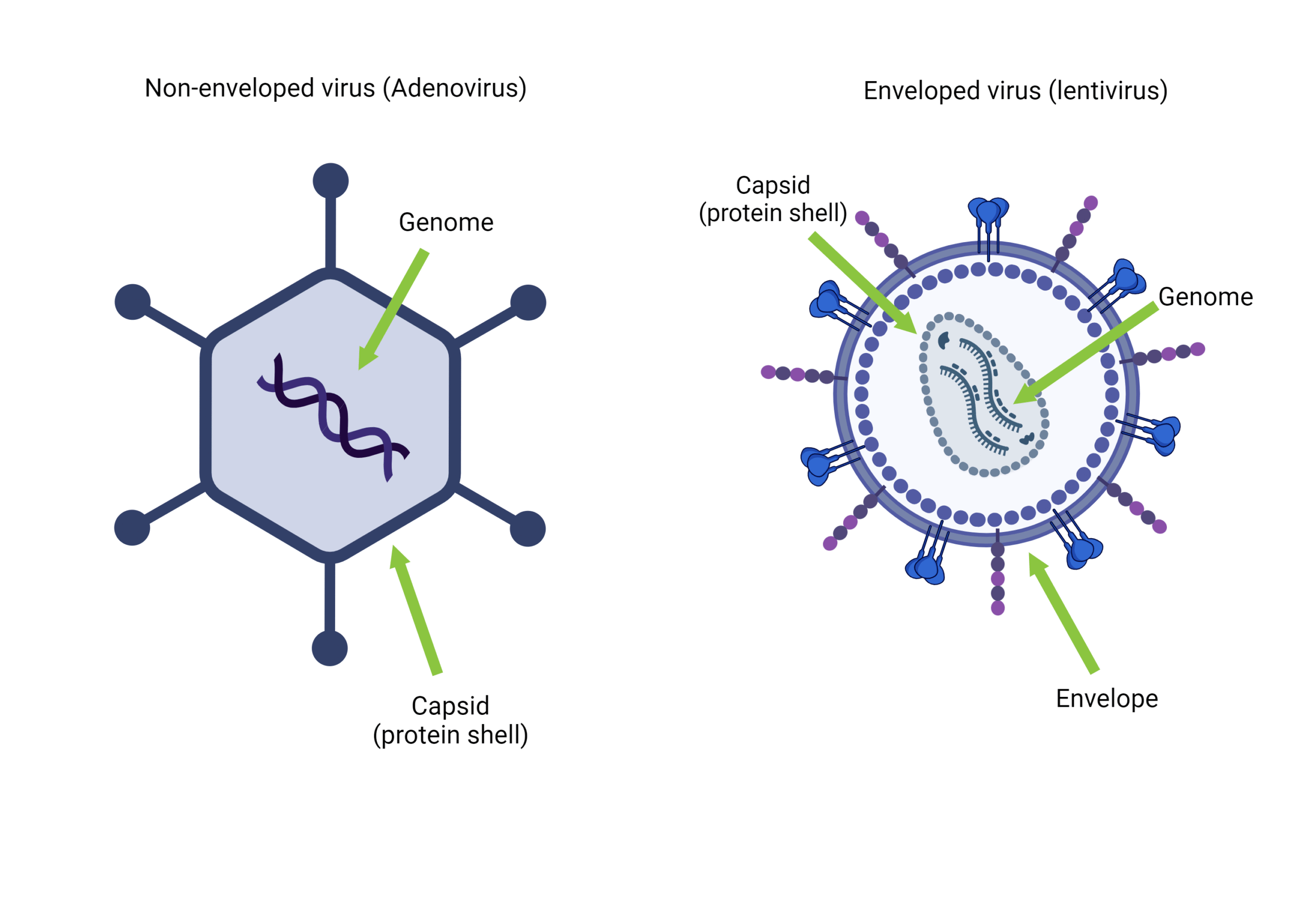

[…] are viruses that specifically target bacteria. Most phages have a simple structure consisting […]

[…] particles. Don’t get me wrong, this system worked for that time. For instance, families like Myoviridae, Siphoviridae, and Podoviridae were historically grouped based on their morphology, rather than solely on their host organisms. Interestingly, many phages that were once classified […]

[…] all phages reacted the same way to IC. It was effective against several DNA-based phages like T4, T1, and λ. However, IC didn’t work on MS2, an RNA-based phage. This difference led researchers to believe […]