Many people may not be familiar with the term viromics. Viromics refers to the study of viral communities using metagenomic approaches. Metagenomics, in general, is the study of all nucleic acids recovered directly from an environment, without the need for culturing organisms. Although metagenomics technically includes all life forms, it is often used to describe bacterial-focused studies. Viromics challenges this bias by placing viruses at the centre of analysis.

While viromics includes all types of viruses, in most natural environments, the majority of viruses are bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria. Historically, virus research has focused on isolating and studying individual viruses, largely because many viruses are associated with disease. This approach makes sense when the goal is elimination. However, unlike bacteria, which have long been studied as communities, viruses are still in the early stages of community-level investigation, with much of the field recently focused on method optimisation.

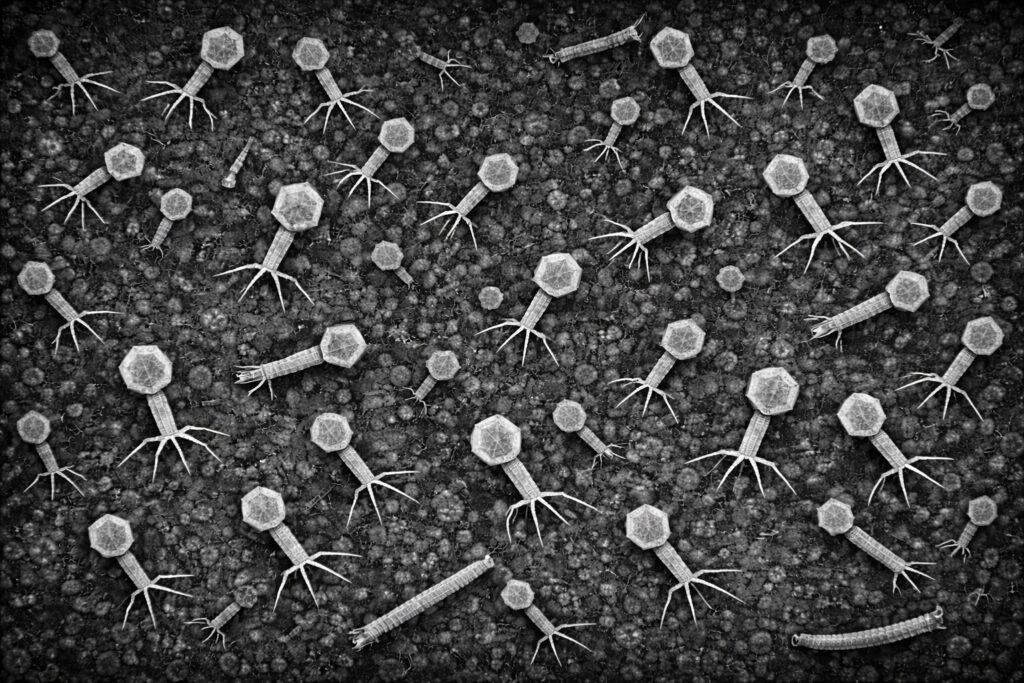

There are growing reasons to question what we may have missed by not studying viruses as communities. Several discoveries highlight the importance of viral interactions. For example, some bacteriophages can prevent superinfection by other phages infecting the same host. In Salmonella, certain prophages must enter the bacterial genome in a specific order for successful infection. Even more strikingly, satellite phages have been discovered that physically attach to other viruses to complete their life cycles, a phenomenon identified by SEA-PHAGES students. These examples illustrate that viral behaviour cannot always be understood in isolation.

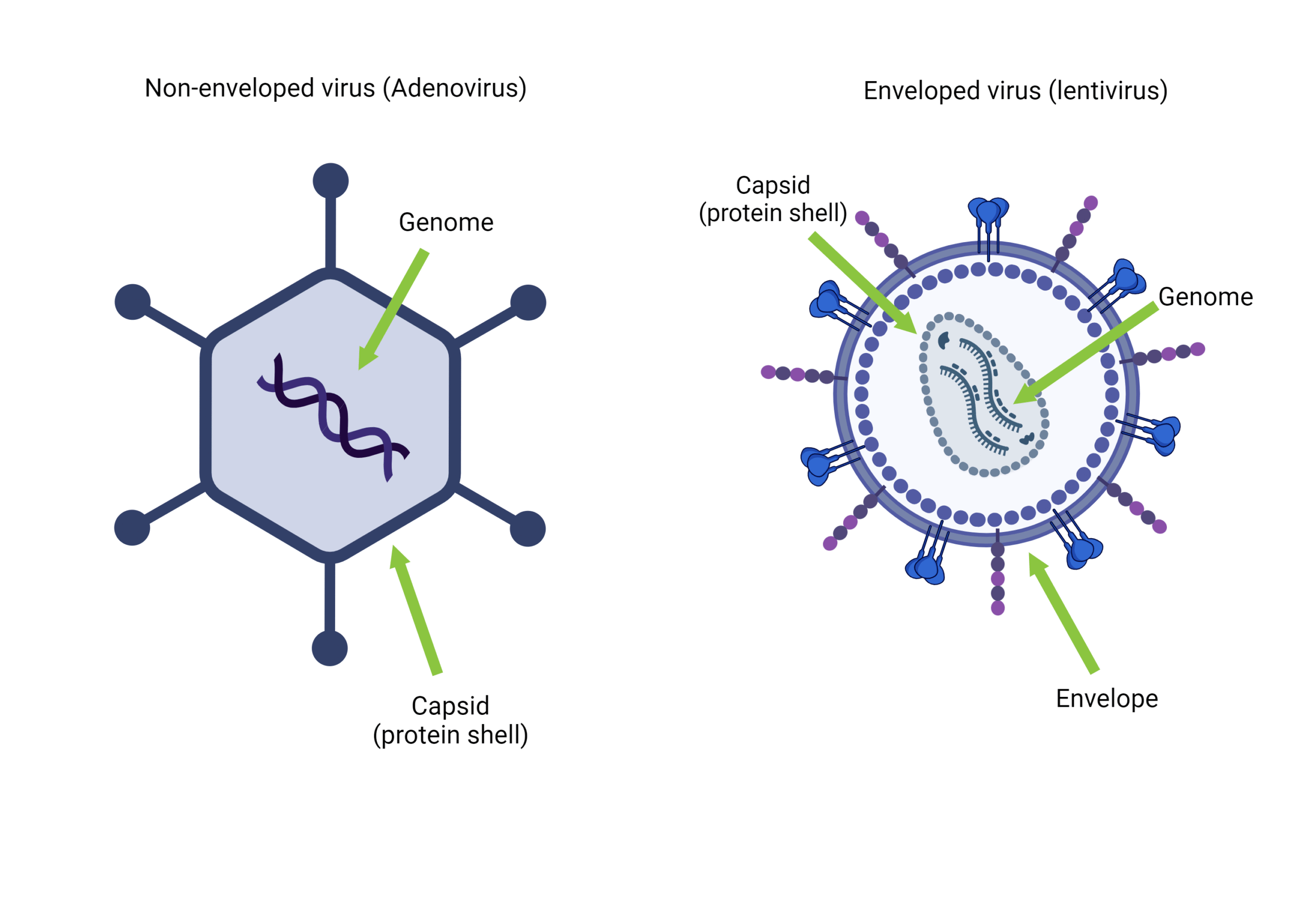

Despite this, viromics remains relatively unpopular. Viruses have long been viewed as lone agents, individual hunters rather than members of complex communities. Research has also been heavily biased toward pathogenic viruses. Technical challenges further complicate viromics: viruses display extreme genetic diversity, can possess DNA or RNA genomes which can be single- or double-stranded, and may contain modified bases that are difficult to sequence. Their small genome sizes also mean viral sequences can easily be outcompeted by host DNA, and integrated prophages are often misidentified as part of bacterial genomes.

As a result, many studies focus only on double-stranded DNA viruses, which are easier to work with and easier to transfer knowledge and methodology from bacterial genomics. Studying RNA and single-stranded DNA viruses or single-stranded genomes typically requires conversion to complementary DNA (cDNA), a process that introduces bias and often results in fragmented genomes (This should be an issue when doing short-read sequencing). This makes it difficult to make accurate abundance or proportional claims in viral metagenomes.

Yet, despite these challenges, viromics offers significant advantages. Some viruses may be beneficial, but their effects often only become apparent within a community context. Studying viral communities also allows clearer links to environmental and physiological factors. Viral consortia could even be harnessed to restore environmental balance or improve host health.

So the question remains: is studying viromics worth the effort?

Given what we are beginning to uncover, the answer may well be yes, especially if we are willing to look beyond individual viruses and embrace the complexity of viral communities.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.