Bacteriophages are increasingly discussed as tools to study, control, or potentially treat infections caused by highly pathogenic bacteria. For scientists new to the field, this naturally raises a critical question:

How can researchers obtain phages for dangerous bacteria without exposing themselves or their laboratories to unnecessary risk?

The answer lies in a principle that underpins modern phage research: scientists almost never begin by working with the dangerous pathogen itself.

Pathogens are not the starting point

Bacteriophage handling is solely dependent on the bacteria used as a host. Highly pathogenic bacteria are subject to strict biosafety regulations and are handled only in specialised containment facilities. Directly culturing such organisms is reserved for cases where it is scientifically unavoidable, such as late-stage clinical validation.

For discovery-driven research, education, and early-stage studies, phage scientists rely on risk-minimised experimental design, allowing meaningful progress without compromising safety.

Using safe bacterial surrogates (critical step in minimising risk)

Instead of culturing the dangerous pathogen directly, scientists often use safe bacterial surrogates. This strategy is central to phage isolation workflows and reflects a deep understanding of how phages interact with bacteria.

Attenuated strains (weakened, non-virulent)

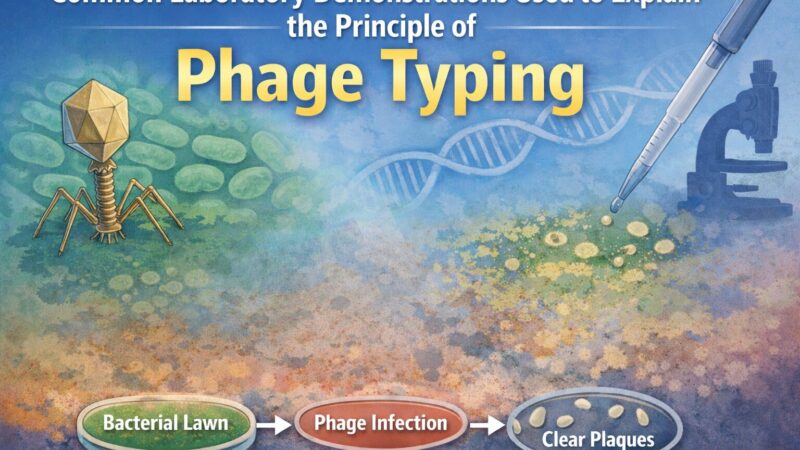

Attenuated strains are bacteria that have lost their ability to cause disease but still retain key biological features of the pathogenic organism. Because phage infection depends on bacterial surface structures rather than virulence, these weakened strains can support phage replication while posing minimal risk to researchers.

Avirulent laboratory strains with the same surface receptors

Many phages recognise highly specific receptors on the bacterial surface. Scientists take advantage of this by using well-characterised laboratory strains that express the same receptors as their pathogenic counterparts. If the receptor is present, the phage can bind and infect—even if the host strain itself is harmless.

Genetically modified strains expressing only the pathogen’s receptors

In some cases, bacteria are engineered to express only a single surface feature relevant for phage binding. This highly controlled approach allows researchers to isolate and study phages targeting specific pathogenic traits without introducing other virulence-associated factors into the system.

Closely related non-pathogenic species

Closely related bacterial species often share structural and genetic similarities with pathogenic strains. These relatives can act as effective stand-ins during phage isolation, enabling discovery while remaining within standard laboratory biosafety levels.

Together, these approaches allow scientists to isolate phages that are biologically relevant to dangerous pathogens, without ever culturing the pathogen itself.

Environmental sourcing without pathogen exposure

Phages are abundant wherever their bacterial hosts exist. As a result, environments such as wastewater, soil, and animal-associated ecosystems may also be contaminated. While it is not always known whether samples contain pathogenic bacteria, they are typically handled using appropriate biosafety precautions until the risk is reduced.

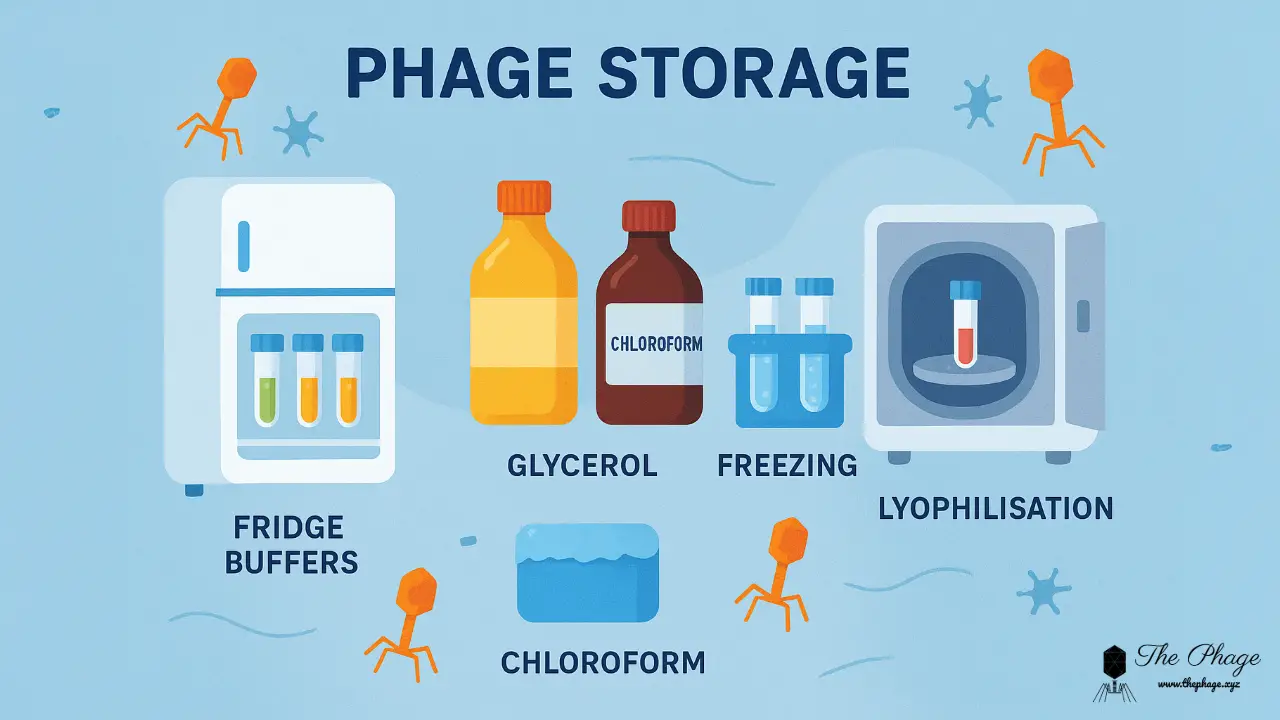

Initial processing steps, such as centrifugation and filtration, are used to remove bacteria and other larger cells while allowing phage particles to pass through. Although filtration substantially reduces biological risk, it does not render samples sterile, and additional safety considerations may still apply.

Depending on the phage type and downstream application, chemical treatments such as chloroform may be used to inactivate remaining bacterial cells. However, this step must be applied cautiously, as chloroform can also inactivate certain phages, particularly those with lipid envelopes.

Once these risk-reduction steps are complete, safe alternative host strains, rather than the pathogenic bacterium itself, can be used for phage isolation, enrichment and characterisation under reduced biosafety risk.

When direct pathogen work is required

There are circumstances, particularly in clinical or regulatory contexts, where phages must be tested against the actual pathogenic strain. When this occurs, work is conducted under strict containment, regulatory approval, and institutional oversight.

Importantly, this stage comes after phages have been identified, characterised, and validated using safer systems.

Genomics further reduces risk

Modern phage research increasingly relies on genome-based discovery. Metagenomic sequencing and computational host prediction enable scientists to identify candidate phages without culturing bacteria at all. This genome-first approach is especially valuable for high-risk or difficult-to-culture pathogens and continues to reshape how the field operates.

Phage science advances not through risk, but through strategy. Understanding how researchers safely obtain phages for highly pathogenic bacteria is a foundational step into the field.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.