Whenever we think of bacteriophages, we are often faced with very different perspectives on whether they are “good” or “bad.” Interest in using these viruses to treat bacterial infections has increased dramatically, largely due to the global crisis of antibiotic resistance.

But there is another perspective that places bacteriophages much closer to our everyday health, beyond treatment. What if phages could help prevent infection in the first place?

To understand this, it helps to start with the broader role of bacteriophages in the environment. One of their primary functions is to regulate bacterial populations. This regulation does not happen through predation alone. Phages can also make bacteria stronger and more adaptable by transferring genes that help them survive in specific environments. In this sense, phages can be both beneficial and harmful, even from a bacterium’s point of view.

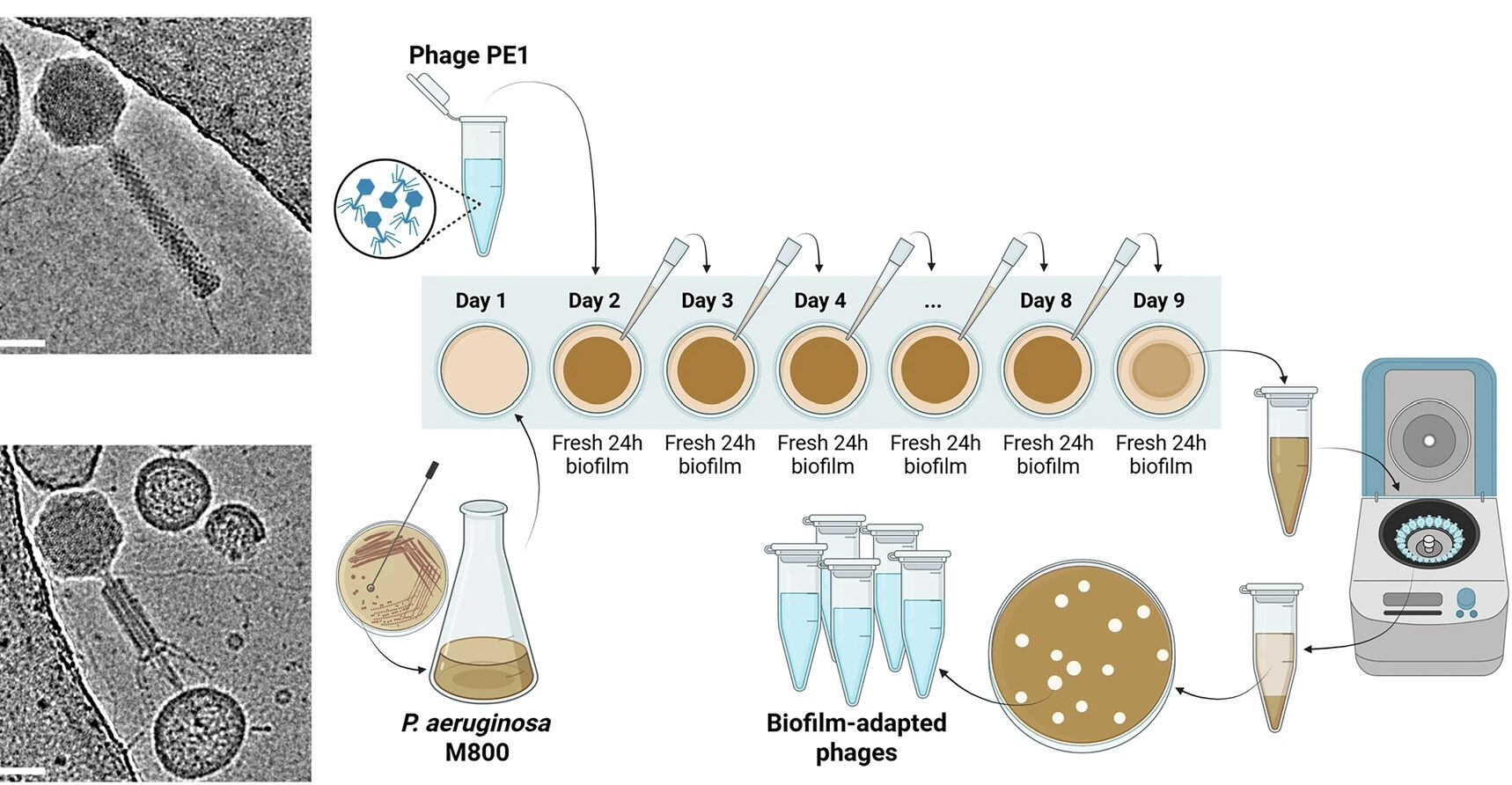

One way phages control bacteria is through the lytic cycle, where they infect a bacterial cell, replicate, and cause the cell to burst, releasing new viral particles that go on to infect other bacteria. Another strategy is lysogeny, where phages integrate their DNA into the bacterial genome and replicate alongside the bacterium as it divides. In return, these integrated phages can provide benefits, such as genes linked to virulence, persistence, or protection against infection by other phages, a process known as superinfection exclusion.

Just like other environments, the human gut is a complex ecosystem dominated by bacteria and viruses. Remarkably, over 90% of the viruses in the gut are bacteriophages. This ecosystem plays a critical role in maintaining host health. When the gut ecosystem is disturbed, signs of imbalance can appear, sometimes developing into disease. Many conditions have been linked to gut dysbiosis, highlighting how important it is to maintain a healthy gut microbiome.

One common strategy to support gut health is to use components of the gut’s own microbial community. This is why scientists are actively working to define what a “healthy” microbiome looks like. By understanding this baseline, it becomes possible to restore or maintain balance when things go wrong.

Phages may become part of this strategy. Rather than acting only as treatments, they could work as supplements helping to stabilise the gut ecosystem, particularly in cases where beneficial phages are reduced. This idea opens the door to phagebiotics: the use of bacteriophages as tools to support and maintain gut health, rather than just fighting infections. Several companies have already begun exploring the use of bacteriophages to support gut health. In the near future, we may see vitamin-like supplements based on phages, or formulations that combine bacteriophages, vitamins and beneficial bacteria.

The question is no longer whether phages matter to human health, but how we can responsibly harness them to keep us well.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.