Why this study matters

One of the biggest obstacles to curing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is its ability to hide silently inside CD4⁺ T cells. Even with effective antiretroviral therapy, these latently infected cells persist and can rapidly reinfect if treatment is stopped. Finding a way to selectively wake up latent HIV—without triggering dangerous, global immune activation—remains one of the central challenges in HIV cure research.

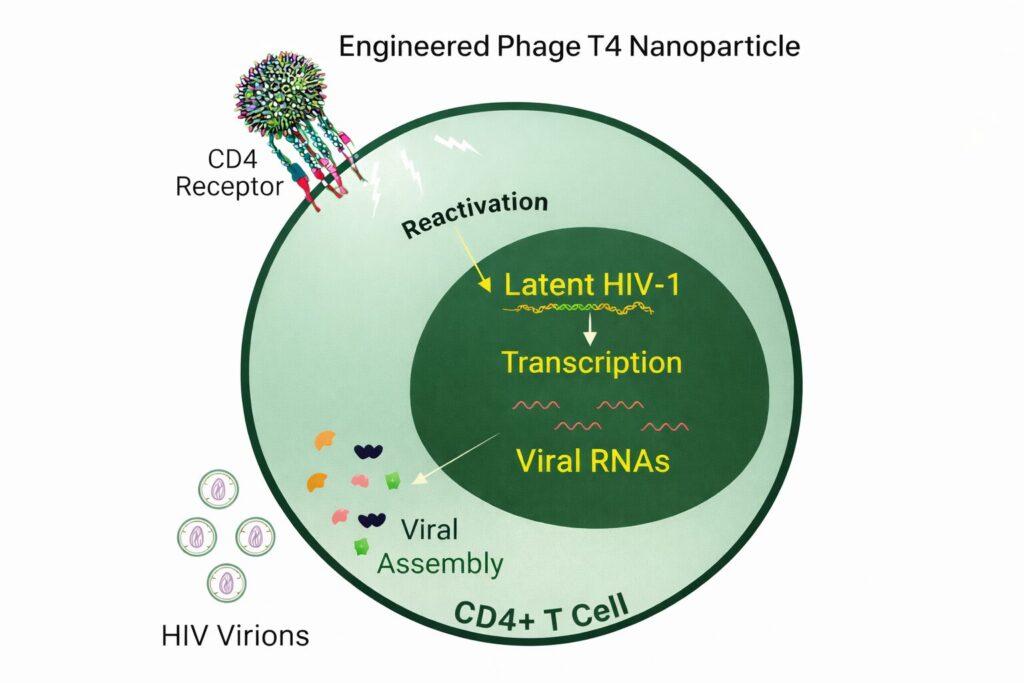

That is what recent publications aimed at solving using an unconventional but elegant approach. They repurpose bacteriophage T4 into a CD4-targeted nanoparticle that mimics key features of HIV itself, nudging latent virus out of hiding in cell models while avoiding broad T cell activation.

Key takeaways

- Bacteriophage T4 capsids were engineered into CD4-targeted nanoparticles

- These particles reactivated latent HIV-1 in established T cell latency models

- Activation was selective, not global, and showed minimal cytokine release

- Reactivation occurred independently of classic PKC and NFAT pathways

- The work is proof-of-concept, but highlights phages as programmable immune tools

The problem with current “shock-and-kill” strategies

The idea behind shock-and-kill is straightforward: reactivate latent HIV so infected cells become visible, then eliminate them through immune clearance or viral cytopathology. In practice, however, most latency-reversing agents lack precision. Many activate large numbers of T cells, induce inflammatory signalling, or risk cytokine storm, limiting their clinical usefulness.

What’s missing is targeted activation, a way to engage CD4⁺ T cells specifically, without pushing the entire immune system into overdrive.

Turning a bacteriophage into a CD4-targeting nanoparticle

Scientists turned to phage T4, a well-studied bacteriophage with a large, stable capsid and a surface that can be densely decorated with engineered proteins. Two T4 surface proteins, Hoc and Soc, function as molecular “display arms,” enabling the presentation of foreign ligands in highly repetitive, multivalent arrays.

Using this platform, the team created HIV-mimicking nanoparticles by decorating T4 capsids with:

- a CD4-binding DARPin, or

- the HIV-1 envelope gp140 trimer

Both designs aim to cluster CD4 receptors on the T cell surface, mimicking how HIV engages its target, without introducing infectious virus.

Do these phage nanoparticles actually wake up latent HIV?

To test this, the researchers exposed engineered T4 nanoparticles to J-Lat cells, a widely used model of HIV latency. These cells carry silent, integrated HIV genomes that switch on a fluorescent signal when reactivated.

The result was striking:

- CD4-targeted T4 nanoparticles induced robust latency reversal

- HIV transcription increased

- Viral proteins and RNA were released into the culture supernatant

Crucially, multivalent display mattered. Soluble CD4-binding proteins alone triggered only weak activation. When the same ligands were arrayed across the T4 capsid surface, reactivation was far more efficient, highlighting the importance of receptor clustering, not just receptor binding.

Activation without the usual immune alarms

One of the most intriguing findings is how this activation occurs.

Classic latency-reversing agents often rely on strong T cell signalling pathways such as PKC or NFAT, which are closely linked to global activation and inflammation. In this study, inhibitors of those pathways blocked standard activators, but did not block phage-mediated reactivation.

Even more importantly, when tested in primary human PBMCs and resting CD4⁺ T cells, the nanoparticles:

- showed minimal Th1/Th2 cytokine production

- did not induce markers associated with cytokine storm

- caused subtle activation signatures consistent with targeted, non-global signaling

This suggests that the phage nanoparticles may be engaging non-canonical activation pathways, possibly involving receptor clustering or innate immune sensing, an area that now deserves deeper mechanistic exploration.

The Phage perspective: why this is exciting

From a phage-biology standpoint, many biologists will agree that this work is a powerful demonstration that phages are not just antibacterial tools.

Here, the T4 capsid acts as:

- a programmable protein display scaffold

- a precision immune-engagement platform

- a scalable, non-infectious nanoparticle produced in bacteria

The geometry and symmetry of the phage capsid enable biological effects—like receptor clustering—that are difficult to replicate with soluble molecules or many synthetic nanoparticles.

This positions engineered phages as a new class of cell-targeted immuno-nanomaterials, with potential applications far beyond HIV.

Limitations and what comes next

As the authors emphasise, this is proof-of-concept work. The latency reversal shown here is based primarily on cell line models and healthy-donor cells. Critical next steps include:

- testing in ART-suppressed patient-derived CD4⁺ T cells

- evaluating efficacy and safety in vivo

- defining the exact signaling pathways involved

Understanding long-term immune effects, dosing, and immunogenicity will be essential before any translational leap.

This study shows that engineered bacteriophage T4 nanoparticles can selectively engage CD4⁺ T cells and reverse HIV latency—without triggering global immune activation.

It’s a compelling example of how phage engineering, multivalent display, and viral mimicry can be combined to tackle one of the most stubborn problems in virology. Whether this strategy ultimately contributes to an HIV cure remains to be seen—but it clearly expands the toolkit for both phage biology and targeted immunotherapy.

Read more: Batra, H., Zhu, J., Jain, S., Ananthaswamy, N., Mahalingam, M., Tao, P., Lange, C., Hill, S., Zhong, C., Kearney, M. F., Hu, H., Maldarelli, F., & Rao, V. B. (2025). Targeted bacteriophage T4 nanoparticles reverse HIV-1 latency in human T cell line models. iScience, 28(12), 114006.

Cover photo credit: Batra et al, 2025 (with some modification from The Phage)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.