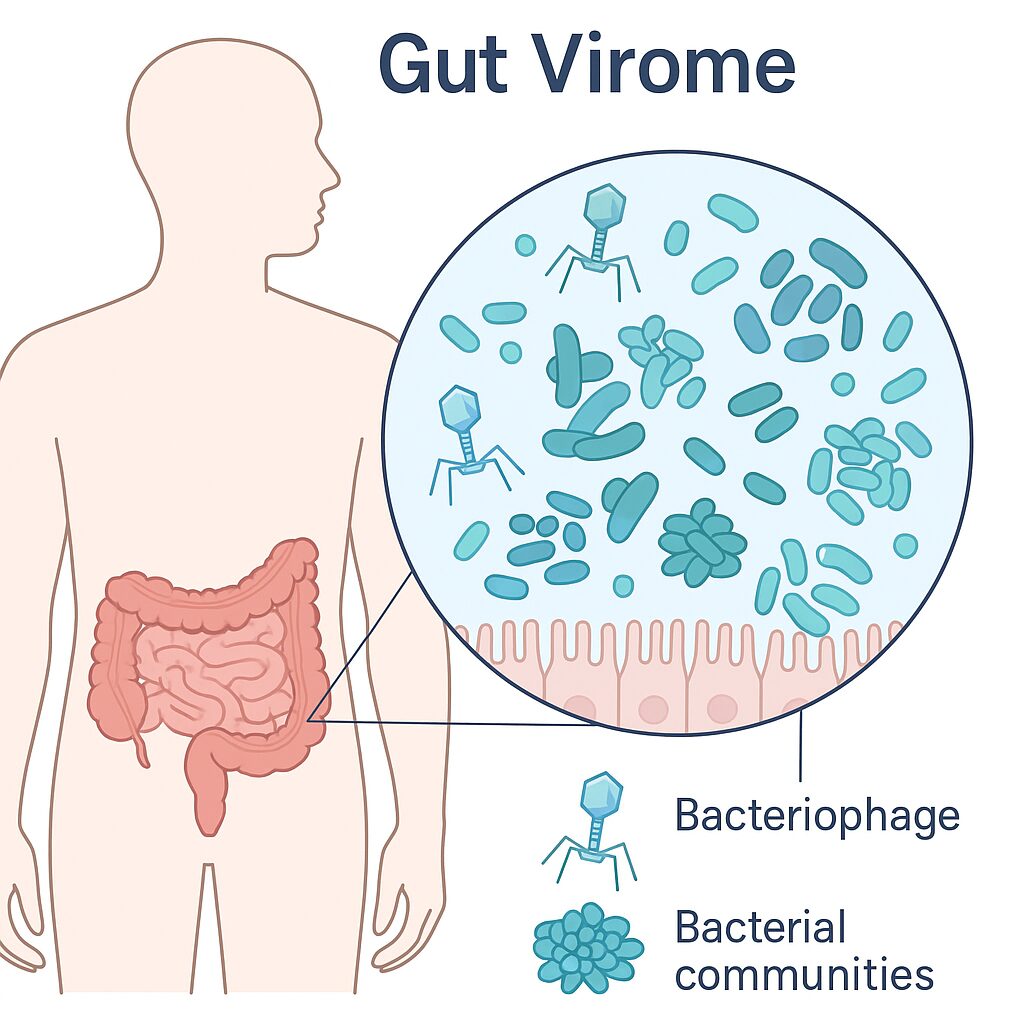

The human gut is home to millions of microbial lives, dominated by bacteria, Fungi and viruses. Despite being one of the prevalent entities in the human gut, viruses have been understudied. The largest portion of these viruses (>90%) is bacteriophages (often referred to as phages), viruses that infect bacteria. Phages form a complex ‘frenemy’ relationship that shapes our digestion, immune system, and overall health. Normal gut flora (microbes that call our gut home without making us ill) provides significant protection against pathogens; some unwanted microbes can still infiltrate and cause unintended consequences.

Some of these microbes are bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics, significantly impacting the way they respond when treated with antibiotics. Bacteria can develop this kind of resistance to more than one kind of drug. This widespread resistance has accelerated the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens. Recent reports suggest that phage and related technologies can effectively target MDR pathogens. While this kind of therapy has already shown promising results against MDR infections, researchers continue to pursue improved outcomes through the development of novel combinational strategies.

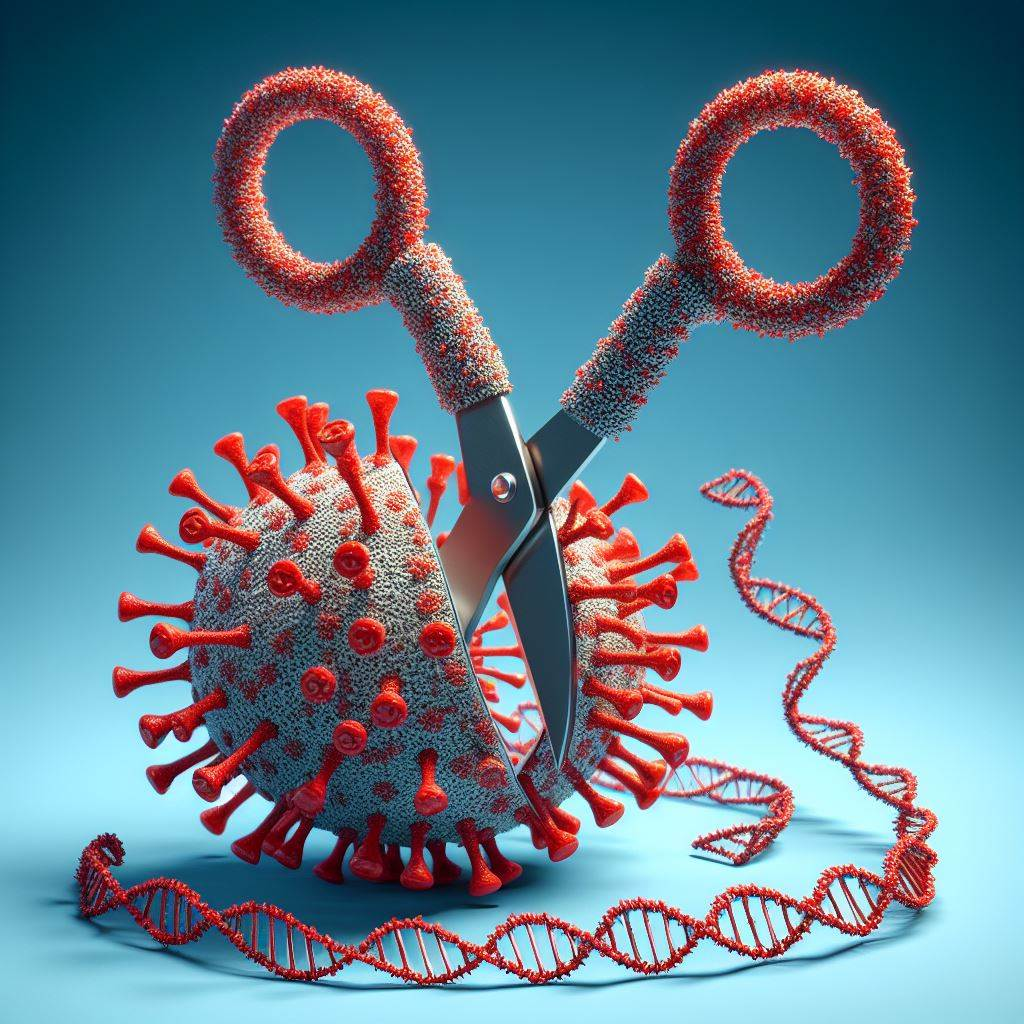

To address the limitations of existing antimicrobial approaches, scientists have turned to the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) system as a gene-specific antimicrobial tool. The CRISPR-Cas system offers a major advantage over traditional therapies due to its exceptional specificity and its ability to precisely delete or disrupt target genes, including those conferring antibiotic resistance.

Although CRISPR-Cas is a powerful gene-editing technology capable of reducing pathogenic bacterial populations through targeted genomic deletions, efficient delivery remains a significant challenge. Phages, as natural DNA delivery vehicles to bacteria, offer a solution to this problem. Beyond naturally infecting bacteria, they can be engineered to deliver CRISPR DNA into bacterial cells.

Phages: More Than Just Gut Viruses

Phages live throughout the gut, and each person carries a unique collection of them. Rather than acting solely as bacterial killers, phages actively shape which bacteria grow and how the gut ecosystem functions. In this sense, you can think of them as tiny soldiers that monitor the bacterial population.

Unlike many destructive viruses, most gut phages are “temperate,” meaning they integrate into bacterial DNA and live alongside their hosts rather than killing them immediately.

- These phages can remain inactive for long periods.

- However, stress, diet changes, or medications can activate them and trigger new virus production.

As a result, this ongoing balance keeps the gut stable while still allowing it to adapt when needed. It works like a neighbourhood watch—usually calm, yet ready to respond when situations change.

How the Gut Virome Changes Over Life

Research on infants shows that the gut’s viral community shifts significantly as people grow:

- Early life: Many active phages roam freely, attack bacteria, and shape the early microbiome.

- Later infancy: Phages increasingly integrate into bacterial DNA, forming long-term partnerships.

- Adulthood: Most phages remain stable and integrated, quietly influencing bacteria.

- Old age: The return of the lytic phages’ dominance

These changes matter because early-life interventions may have greater effects while the virome remains flexible. In contrast, the adult gut already maintains a stable and unique ecosystem, so any changes must respect this established balance.

Phages Maintain Gut Stability

Even inactive phages can suddenly activate and release new viruses when triggered by diet, medications, or inflammation. These occasional bursts play an essential role; they prevent any single bacterial group from dominating. In other words, nature uses phages as a quality control system that preserves gut health without causing harmful disruption.

Identifying “Who Infects Whom”

Phages, like many other viruses, have a high level of specificity. Using advanced tools, it is possible to pinpoint which phage infects which bacteria. This progress matters greatly because it allows researchers to:

- Understand how phages shape bacterial communities more clearly

- Design CRISPR-based therapies with precise targets

- Ensure engineered phages infect only the target bacteria

Therefore, this knowledge serves as a map guiding safe interventions in a delicate ecosystem. Without such clarity, changes could cause unintended consequences.

CRISPR: A Tool for Precision Gut Editing

CRISPR allows scientists to edit genes with exact precision. Originally a bacterial defence system against phage infection, CRISPR now enables targeted DNA changes in many settings. In the gut, researchers use CRISPR in two primary ways:

1. CRISPR-Carrying Phages

These phages act like delivery trucks, bringing CRISPR into bacteria to:

- Reduce antibiotic-resistant and virulent strains of bacteria

- Target only problematic strains

2. CRISPR Inside Temperate Phages

Scientists also use CRISPR to control when temperate phages activate. This approach helps:

- Maintain microbial balance

- Reduce harmful viral bursts during inflammation

- Intentional targeting of unwanted bacteria

Ultimately, researchers aim to use CRISPR and phages to support the gut’s natural ecosystem. Because the gut virome is both complex and stable, interventions must work with, not against, its structure.

The Future of Gut Health

Research points toward a future where:

- Personalised virome therapies match each person’s unique gut.

- Safe phage-based treatments preserve microbial balance

- CRISPR-guided gut engineering treats infections, reduces harmful bacteria, and improves metabolism

Phages already quietly shape bacterial communities and gut function. Now, thanks to ongoing research, we understand how the virome develops, how phages interact with bacteria, and how CRISPR can guide safe interventions. Therefore, as we move into a new era of microbiome medicine, these advances offer hope for safer, more personalised treatments and the potential to transform human health.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.